The latest articles

Happy anniversary to Hemingway's In Our Time

Every year is the anniversary of some important piece of art, as record companies are only too happy to remind us these days. With 2015 coming to a quick close, I’d like to celebrate the 90th anniversary of my favorite book: Ernest Hemingway’s In Our Time.

Note how I say “book” and not “novel” or “short story collection.” Most sources will tell you that In Our Time is the latter, and only those prepared to make an argument will claim it's the former. Perhaps D. H. Lawrence said it best when he called it a “fragmentary novel.”

I can certainly make arguments one way or the other. The “short story collection” argument is not all that hard to make because, at its core, In Our Time is comprised of several of Hemingway’s earliest short stories, many of which had been previously published in magazines and literary journals. But it’s the overall effect of reading In Our Time as a unified, complete work that makes it a staggering experience for me, every single time I’ve read it in the past 25 years or so.

Making the case for In Our Time as (an admittedly experimental) novel is not only the esteemed Mr. Lawrence mentioned above, but also the author, Papa Hemingway himself. He said that to change one single word would be to ruin the experience he designed for the reader. While these stories are not necessarily linked to each other, they are meant to evoke the experience of the early 20th century. It explores how World War I changed the world, and how it affected individual people.

It helps that there is a particular individual who keeps popping up throughout the pages of In Our Time, and that’s Hemingway’s thinly veiled alter-ego, Nick Adams. Especially early on, and near the end, Nick is the protagonist of many of these stories, and it’s not hard to discern a pattern: Nick is growing up and constantly being disillusioned. In the first Nick Adams story, he witnesses a suicide during an outing that should have been great father-son bonding time, and in the second, he sees his father in a whole new, wholly unflattering light. Nick makes his way to the war, and by the end of the book, he’s trying to recover from the attendant trauma by spending time alone fishing by the river.

What breaks up the coherency are the stories in the middle, many of which are fragments of life during wartime in Europe. Is Nick a witness to these events? I’d like to think so, but it’s never explicitly stated. Is Nick the young soldier in “A Very Short Story” who falls in love with his Italian nurse, only to come home to Chicago and find a Dear John letter from her, later recovering from heartbreak by picking up the clap from a one-night stand? The benefit of hindsight, and the knowledge of the love affair between Hemingway and his nurse Agnes von Kurowsky, say that yes, this is probably another Nick Adams story.

Perhaps most confusing and/or off-putting to the first-time reader is the very device that Hemingway uses to unify the book–the short “chapters” in between the stories. Most are explicitly scenes from the war; some are about bullfighting; they’re all generally horrific. Yet it’s hard to pick out any narrative thread from them. But that’s what makes this a fragmentary novel. War is jarring and disorienting, and has no easy answers.

On the other hand, on the side of those who simply label this a short story collection, there is the previously mentioned fact that most of these stories were published before. They were written over many years, and saw publication in many different places. When a publisher collects these types of stories and puts them all in one book, that’s the very definition of “short story collection.”

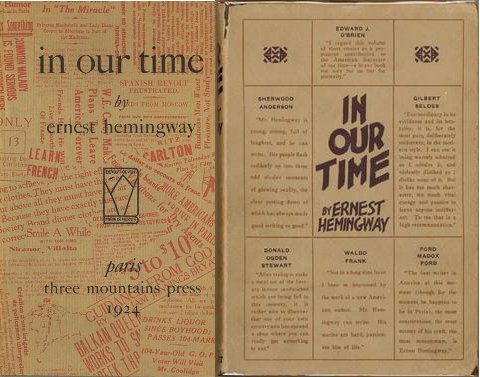

And there’s also the fact that despite Hemingway claiming that one little word being changed or omitted could change the intent of his first major book, he tinkered quite a bit with In Our Time. The first edition had a very small print run in Paris, in 1924–and that version was called in our time (notice the lack of capitalization). This version lacked two of the book’s best known and most well-loved stories, “Indian Camp” and “Big Two-Hearted River,” amongst others that didn’t make the cut this time around. The more familiar (and fully capitalized) In Our Time was printed in New York in 1925, yet it was still missing a famous piece: the opening story “On the Quai at Smyrna” didn’t appear until a revised edition in 1930.

So much for one word changing the whole meaning of the book. And maybe the anniversary I’m celebrating should be the 85th, as it’s the 1930 version that I’ve known and loved, and of which I possess several different printings.

In the end, I suppose it’s not all that important how you read my favorite book. If you want to skip straight ahead to “The Three Day Blow” or “A Very Short Story,” feel free. If you want to read it like I do–as one of the most experimental novels by a major American writer–I’d be very happy for you. It may not become your favorite book, but you may like it enough to one day stop and note the anniversary of its publication.